We’re using closed cell foam for insulation on all exterior walls and in the roof (which also has rigid foam). If you’ve ever been on a boat and seen foam cushions that have a smooth shiny surface to them – that’s closed cell foam. Open cell foam is more like a sponge. Closed cell foam doesn’t absorb water, but open cell foam does.

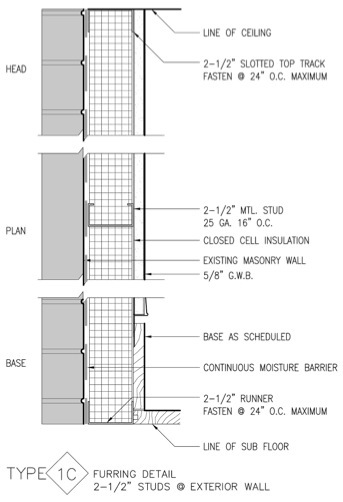

When our architect spec’d things he said there should be a moisture barrier between the foam and the brick wall. Here’s his detail…

Notice his note for a “continuous moisture barrier”. Basically “moisture barrier” is a fancy term for a sheet of plastic – there’s not much high tech about it.

Notice his note for a “continuous moisture barrier”. Basically “moisture barrier” is a fancy term for a sheet of plastic – there’s not much high tech about it.

Well, when the contractor started framing the walls he didn’t put up the moisture barrier. He hadn’t really noticed it in the drawings and on other projects the moisture barrier had gone on the inside of the studs – between the studs and the drywall. We tried to push back, but wound up giving in. Since closed cell foam is a moisture barrier we said he could skip the moisture barrier if he wanted to.

Not putting the moisture barrier in has turned out to be a bad decision on the part of the contractor. He had the insulation subcontractor in today and she said the brick will absorb the equivalent of 1 1/2 inches of closed cell foam. So to get 2 1/2 inches of depth she has to spray 4″ of insulation (which means she’ll charge for 4″ of insulation).

I also worry about what all that absorbed foam will do to the brick, so I’ve asked the contractor to put the moisture barrier in. It won’t be very easy now that there’s all sorts of plumbing and wiring in place, but it sorta just needs to be done…

So word to the wise – if you’re using foam insulation, put a moisture barrier over your brick before you start framing the walls.

Both sprayed foam and polyiso rigid foam are from the same family of closed cell foam; they differ in technique – the former is done on site while the latter factory fabricated in panels.

With masonry facade, today’s cracks, crevices and voids maybe be filled and down the road new ones will emerge and turn into water/moisture trap cavities. This leads to the issue of freeze/thaw that you mentioned and much of which has to do with the historical performance of those bricks, i.e. good brick vs. bad bricks, how much water damage has the facade suffered and so on so forth.

In my research for effective brownstone insulation, it makes sense to me to use iso boards with foil facing which acts as a moisture plane to allow wet bricks to dry as they have been doing prior to insulation, and thereby minimizes freeze/thaw consequences When taped and caulked properly, iso boards are highly effective and retain their R values. If the house sheathing was done in plywood instead of masonry then sprayed foam is the way to go.

In your situation I thought in the interest of time, effectiveness and cost, iso boards might be the better solution… I guess I’m questioning whether putting up a plastic vapor barrier next to a brick wall is a good decision as logically it tells me that bricks will always be wet on the interior side due to either rain or condensation. Searches for “bricks” on GBA website is always helpful.

Jacquie… I still don’t quite follow you… A wood frame house (where you say spray foam is appropriate) will flex more than a masonry structure. More cracks will develop in the wood frame house than in the masonry one, and the wood framing will rot – the masonry won’t.

If I understand you correctly you’re advocating an approach with no vapor barrier – just rigid foam that’s taped. (I don’t really see the foil as a vapor barrier since it’s not continuous). My understanding is that you gotta have a moisture barrier.

Originally our houses didn’t have air conditioning and they were drafty in the winter. As a result the humidity on each side of the wall was about the same and so there was nothing compelling the moisture to travel through the wall. The wall would get wet when it rained, but that was the only moisture issue.

Then air conditioning was introduced and moisture started traveling through the wall from the outside to the inside of the house in the summer. But because the walls were the original plaster walls and plaster is resistant to mold, that wasn’t a huge problem. It wasn’t happening in winter, so the moisture wasn’t freezing and thawing and destroying the brick (from within).

The issue is that these days the buildings are better insulated and far more air tight. As soon as that happens moisture is compelled to travel through the brick in the middle of winter – from inside the house outwards. As the moisture gets to the outside of the brick it turns to ice and expands. The expansion basically destroys the brick from within – you’ll see spalling and over time the brick just disintegrates. Another tell tale sign is white residue on the brick.

The only way to stop that is with a continuous vapor/moisture barrier. My understanding (based on what I described above) is that they’re not optional in a well insulated house. Ideally you put the moisture barrier and insulation on the outside of the brick so the brick stays above freezing and freeze/thaw isn’t an issue, but clearly that’s not possible in our case. Our long wall is on the lot line, and the front and back walls can not be covered over on the outside. So the best you can do is put the moisture barrier on the inside. Plastic sheeting works, but closed cell foam is a moisture barrier as well. I just don’t like the idea of something getting into the brick and expanding – whether it be foam or water that’s freezing, so plastic sheeting is our desired moisture barrier. But in our case we’re doing it after the fact now so the plastic will be less of a moisture barrier and more of a barrier to prevent the foam from getting into the brick.

Yes, the outside of the wall will get wet and some will penetrate the rather porous historic brick, and the only way it will be able to drain out of one side of the brick – but that’s sorta the case with any house with a moisture barrier. But rain has been an issue for 127 years – it’s just a fact of life – and vast majority of it has drained back out through the exterior (now all of it has to drain out the exterior). We’re not trying to stop that – we’re trying to stop humidity in the home migrating through the walls in winter.

Then there’s actual performance of the insulation. Rigid foam and closed cell foam can have the same R value on paper, but in the real world closed cell foam is far superior. I’ve seen discussions about how just a flash coat of closed cell foam can outperform rather thick installs of traditional insulation because it stops drafts so effectively. That’s why LEED certified houses are pressure tested with blower doors – stopping drafts is a big deal. If you don’t do it with closed cell foam you have to do an incredible job with your moisture/vapor barrier.

All of that said – we are using rigid foam in the roof. There are 4 inches of rigid foam above the roof deck and 4 inches of closed cell spray foam in rafters under the roof deck. In the bulkhead both the rigid and spray foam are in the rafters.

Jay, perhaps it will interest you that I found your explanation extremely helpful to the novice homeowner. It was readable and clear. We are dealing with water damage that damaged the sheathing of our home with a brick exterior. Thanks to you, I now understand the CONCEPTS behind the choices the contractors are presenting us. That is golden.

I should probably mention that the spray foam installer who finally did the work contradicted the first estimate. He said there isn’t a problem with absorption into the brick. So we did spray the foam directly on the brick and haven’t noticed any problems so far (4 years later).

Jacquie… After writing that other big long response… The quick answer is that what I’m advocating is a moisture barrier (up against the brick) + closed cell foam. The moisture barrier sorta solves the cracks issue you’re talking about – the plastic sheeting won’t crack, and closed cell foam will get into nooks and crannies better than rigid insulation can.

Jay,

I’m a bit late to this conversation, but I wanted to orient you to THE knowledge source :

http://www.buildingscience.com/documents/digests/bsd-114-interior-insulation-retrofits-of-load-bearing-masonry-walls-in-cold-climates

Folks like Drs. John Straube and Joseph Lstiburek and the rest of the Building Science Corp. team are where I turn when addressing complex hygrothermal conditions in a building’s envelope.

In a double wythe brick with plaster applied onto the brick in a 2 story building near Lexington Ky. What is the best approach to insulate the inside with rigid insulation board

Jay, I hope you still follow this blog. Thousands of homes were flooded during Hurricane Harvey in Houston and now we are forced to remove the Gypsum board, installed as a moisture barrier back in the 70’s. Since you sprayed closed cell foam directly to the brick, my question is if you had experienced any issues since your last post in October 2015. Do you see any issues spraying closed cell foam directly to the brick in Houston (hot and humid)?

Closed cell foam is a vapor barrier. I know there are different rules about where you put the vapor barrier for warm climates and cold climates. So can’t speak to what to do in Houston. And I’m guessing if you already have another vapor barrier, I’m guessing anything between the two will rot if moisture gets in there.