Did the title get your attention? Good… This is pretty important…

It’s amazing how much we didn’t know when we bought our place. I was doing TONS of research, thought I knew a fair amount, but first I didn’t know we were buying into the roughest block in the neighborhood, and now I find out there are government programs that will pay up to 40% of our renovation costs. 40% makes a REAL difference and we had no clue when we went into contract… If we had picked the “wrong” building we would have gotten nothing.

Last night I went to a “town hall forum” run by state senator Bill Perkins on tax credits for renovating historic buildings. Luckily (for us) our townhouse is in an area that’s on the National Register of Historic Places. Being in that area is what qualifies us for the tax credits. You also have to be in a census tract that is below the average income in New York State ($51,000). Nearly all of Senator Perkins’ district is below the NY state average income – some 1600 buildings qualify for these credits. HOWEVER, next year they’ll be changing over to 2010 Census data and there’s no guarantee that those buildings will qualify next year. So you should take action pretty quickly to get this money.

Here’s how it breaks down… There are state and federal programs and they’re divided into “homeowner” and “commercial”. “Commercial” means anything that produces income – including rental apartments in a townhouse. In general you can get 20% for homeowner and 40% for commercial. (There’s also a 10% credit for old, but non-historic buildings, but it can’t be used for residential buildings.) There is a max credit of $50,000 for the homeowner credit, and $5M for the state part of the commercial credit, but the federal commercial credit is unlimited.

In both cases there are stipulations… For starters these credits are for historic buildings so they’ll only pay for things that are done inside the historic building envelope. They won’t pay for the fence along the street, they won’t pay for a new sewer connection, the won’t pay for a deck on the back of the building, etc. But they will pay for pretty much everything else. The other big stipulation is that you must follow federal guidelines when doing the renovation (as defined by the Secretary of the Interior and the National Park Service). There are 10 guiding principles which are worth repeating here…

- A property shall be used for its historic purpose or be placed in a new use that requires minimal change to the defining characteristics of the building and its site and environment.

- The historic character of a property shall be retained and preserved. The removal of historic materials or alteration of features and spaces that characterize a property shall be avoided.

- Each property shall be recognized as a physical record of its time, place, and use. Changes that create a false sense of historical development, such as adding conjectural features or architectural elements from other buildings, shall not be undertaken.

- Most properties change over time; those changes that have acquired historic significance in their own right shall be retained and preserved.

- Distinctive features, finishes, and construction techniques or examples of craftsmanship that characterize a historic property shall be preserved.

- Deteriorated historic features shall be repaired rather than replaced. Where the severity of deterioration requires replacement of a distinctive feature, the new feature shall match the old in design, color, texture, and other visual qualities and, where possible, materials. Replacement of missing features shall be substantiated by documentary, physical, or pictorial evidence.

- Chemical or physical treatments, such as sandblasting, that cause damage to historic materials shall not be used. The surface cleaning of structures, if appropriate, shall be undertaken using the gentlest means possible.

- Significant archeological resources affected by a project shall be protected and preserved. If such resources must be disturbed, mitigation measures shall be undertaken.

- New additions, exterior alterations, or related new construction shall not destroy historic materials that characterize the property. The new work shall be differentiated from the old and shall be compatible with the massing, size, scale, and architectural features to protect the historic integrity of the property and its environment.

- New additions and adjacent or related new construction shall be undertaken in such a manner that if removed in the future, the essential form and integrity of the historic property and its environment would be unimpaired.

Curiously, those are not exactly the same standards as the City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) uses. The LPC is much more rules based, where the national system is much more interpretive and subjective so you can get approved by LPC and then rejected by NY State or the National Park Service.

In our case we don’t have to deal with the NYC LPC since we’re not landmarked by the City, so we just have to deal with the federal standards. One of the presenters last night worked for New York State Office of Historic Preservation and is the woman who will probably be the primary person making the decision on our project. I asked her a number of questions many of which were about windows. Her responses say a lot about their decision making process.

The windows we’ve been wanting are tilt-n-turn windows. Normally you wouldn’t think of tilt-n-turns on a historic building, but they can be mulled together in a way that makes them appear from the outside to be double hung window. We realized early on in the process that our window openings are so huge that we need “architectural” level windows. Those don’t come cheap, so we started investigating what our options were and looked beyond the standard choices (Marvin, Anderson, Pella) and had an architect recommend Gaulhofer. Gaulhofer is an Austrian company that only has one distributor in North America (located near Vancouver – if you’re interested, contact Eva and tell her Jay & Dan told you about them). Gaulhofer has VERY high quality windows – they don’t use cheap wood like American window manufacturers do – they use either end grain Spruce or Larch. The wood is stunning actually… I’ve heard a number of people this week talk about how their 100 year old wood windows still work. Well very few of the new American wood windows will be around in 100 years – they’re just not built how they used to be, but a Gaulhofer window just might be.

One of my questions was about the protective metal trim Gaulhofer puts on their wood windows (see the picture to the right). The woman answering my questions didn’t want to make a decision on the spot, but she recommended that we should submit plans with the metal trim in the same exact color as the wood. While she made it clear it would have to be discussed and she might say ‘no’, she said she liked the fact that the metal strips would make the window last longer. She also pointed out that even if she approves it, it could get rejected by the National Park Service. But the point here is that these aren’t preservationists who are inflexible. Unlike the LPC, she has the right to subjectively interpret the federal guidelines and use her best judgment.

One of my questions was about the protective metal trim Gaulhofer puts on their wood windows (see the picture to the right). The woman answering my questions didn’t want to make a decision on the spot, but she recommended that we should submit plans with the metal trim in the same exact color as the wood. While she made it clear it would have to be discussed and she might say ‘no’, she said she liked the fact that the metal strips would make the window last longer. She also pointed out that even if she approves it, it could get rejected by the National Park Service. But the point here is that these aren’t preservationists who are inflexible. Unlike the LPC, she has the right to subjectively interpret the federal guidelines and use her best judgment.

My other major window question was about reflectivity of the glass. Modern “low-E” coatings have a reflective sheen and the National Park Service says at one point in their clarifications that you shouldn’t change the reflective quality of the glass, so I was wondering whether we would be limited in the glass we used in the windows. Well, it turns out changing the reflective nature of window only applies if you’re restoring an old window (or presumably putting a new window next to an original one). Like durability, energy efficiency is something they’ll bend the rules to accommodate – though only so far…

Because the previous owner gutted the building, we don’t have many original details to preserve so we’re allowed to be completely modern in the interior of the building and the federal and state tax credits will cover those modern renovations. In fact, you can see in the guidelines above that they prefer modern details over fake historical details. They want a differentiation between what’s new and what’s old. In our case we need to pay a lot of attention to our cornice and to our stoop – since those are some of the only original details that are left on our building. We will also need to replicate the original security gates (which will be expensive).

Back to the tax credits…

The homeowner tax credit is the easiest to get. It’s 20% of everything you spend on your property that’s inside the original building envelope. Review is also the easiest, especially if you’re like us and don’t need to go through LPC – it’s pretty much reviewed and approved by the woman I met – and she seemed completely reasonable to me. The homeowner tax credit can also be used for little things – like a new roof, new windows, or fixing up your stoop – as long as you’re spending $5,000 or more and at least 5% of the work is exterior work, you’ll qualify. But as I mentioned above the problem is that it’s limited to a max credit of $50K.

Things get more complicated, but potentially more profitable when you go for the commercial tax credit, especially if your building is a mix of an owner’s unit and rental apartments (like ours). For starters, to get the commercial credit you need to determine the current “adjusted basis” of the building. The adjusted basis is the current value of the property, minus any depreciation, minus the value of the land. Then you need to spend at least that amount on the commercial part of your property. The commercial credit is only for really major renovations. Spending the value of the building on just the rental units can be quite difficult – especially in a case like ours where only about 25% of the building will be rental. You do get to include a percentage of the common elements of the building (the roof, the façade, etc.) to your commercial renovation costs. The percentage you can use is the percentage of your building’s square footage that’s “commercial”. To pull all of this off, you’ll probably need an appraiser to determine the adjusted basis, and an accountant to handle all the cost breakdowns – it’s not easy, but you may get a substantial amount of extra money.

One other detail is that you must own the building for 5 years after completion for the commercial credit and two years for the homeowner’s credit – otherwise they’ll want at least some of their money back. However, if you don’t use the entire credit the first year, you an roll it over to subsequent years – up to 20 years on your federal taxes and indefinitely on your state taxes. You also aren’t allowed to change things during those 2 or 5 years – at least not details that were conditions of the tax credit.

These tax credits only help a bit when you get your mortgage. They are considered assets by the bank, not income, so you become a better credit risk, but it doesn’t change your debt-to-income ratio. So somewhat unfortunately you may need to do a more expensive renovation to get the tax credits, but those extra costs may put you beyond your loan limit based on your debt-to-income ratio.

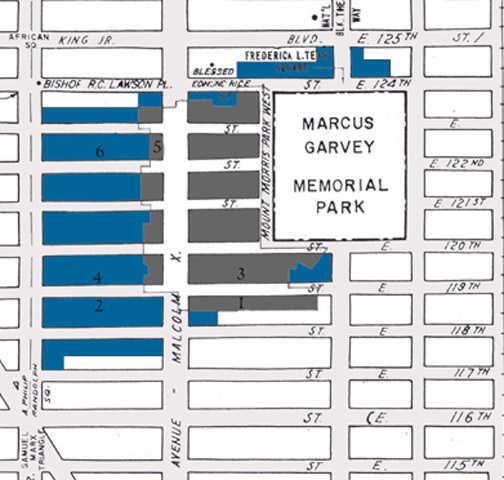

So this is definitely the time to renovate a shell in a historic area. Below is a list of historic districts that are covered. Contact Kathleen Howe at the New York State Office of Historic Preservation (518/237-8643) if you’re not sure if your building is in one of these areas (the City’s landmark boundaries are not the same as the boundaries set by the National Register of Historic Places)…

- Mount Morris Park

- Manhattan Avenue (around 120 to 123)

- St. Nicholas (Strivers’ Row)

- Hamilton Heights

- Sugar Hill

- West 147-149

- Audubon Terrace

- Jumel Terrace

And make sure you start the application process soon. The 2010 Census data may disqualify areas that are currently qualified since Harlem changed so much over the past 10 years.

If you have any questions about these tax credits start by calling the New York State Office of Historic Preservation – 518/237-8643. They’re incredibly helpful and knowledgeable and want to see people using these programs to fix up old buildings.

[And yes, I do understand there’s a certain contradiction in not wanting to be landmarked, but making use of tax credits for historic buildings… More on that in another blog post.]

One of my questions was about the protective metal trim Gaulhofer puts on their wood windows (see the picture to the right). The woman answering my questions didn’t want to make a decision on the spot, but she recommended that we should submit plans with the metal trim in the same exact color as the wood. While she made it clear it would have to be discussed and she might say ‘no’, she said she liked the fact that the metal strips would make the window last longer. She also pointed out that even if she approves it, it could get rejected by the National Park Service. But the point here is that these aren’t preservationists who are inflexible. Unlike the LPC, she has the right to subjectively interpret the federal guidelines and use her best judgment.

One of my questions was about the protective metal trim Gaulhofer puts on their wood windows (see the picture to the right). The woman answering my questions didn’t want to make a decision on the spot, but she recommended that we should submit plans with the metal trim in the same exact color as the wood. While she made it clear it would have to be discussed and she might say ‘no’, she said she liked the fact that the metal strips would make the window last longer. She also pointed out that even if she approves it, it could get rejected by the National Park Service. But the point here is that these aren’t preservationists who are inflexible. Unlike the LPC, she has the right to subjectively interpret the federal guidelines and use her best judgment.